King’s Lynn & West Norfolk Borough Council has told National Highways to apply for retrospective planning permission for a controversial bridge infilling scheme in the borough.

National Highways has been using permitted development rights to fill in old railway bridges in a bid to reduce its maintenance liabilities. However, it has faced opposition from greenway developers, civil engineers and sustainable transport advocates under the umbrella of The HRE Group.

National Highways manages 3,100 legacy rail structures for the Department for Transport – mostly broad bridges that span disused railway routes.

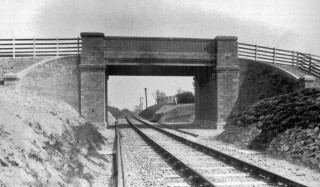

As part of its strategy for looking after these structures, in 2021 National Highway blocked up a bridge at Congham, Norfolk, with hundreds of tonnes of aggregate and concrete. But it failed to seek written consent for the material to remain beyond the maximum 12-month period allowed under powers known as ‘Class Q’. The Borough Council of King’s Lynn & West Norfolk now expects submission of a planning application by mid-March.

Congham bridge spanned the dismantled Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway, which was recently earmarked as the proposed route of a footpath and cycleway between King’s Lynn and Fakenham. National Highways insists, however, that the local highway and planning authorities said they had no plans for use of the route beneath the structure for ‘active travel’ purposes.

Two other local authorities have also taken National Highways to task over its exploitation of permitted development rights to scupper local footpath plans.

Eden District Council in Cumbria has given National Highways until October to remove 1,600 tonnes of infill from a bridge at Great Musgrave, after rejected a planning application for its retention. Meanwhile Selby District Council is expecting submission of a retrospective planning application this week relating to the infilling of a structure near Tadcaster.

Graeme Bickerdike, leading The HRE Group campaign, said: “National Highways has used the same permitted development rights to infill at least six structures in the expectation that nobody would notice or care about its breaches of the statutory obligations therein. But three local planning authorities have now asked for retrospective planning applications whilst another vigorously opposed the work from the outset.”

According to The HRE Group, in September 2020 alone, National Highways sent out 28 template letters seeking to exploit Class Q permitted development rights for infill schemes, asserting that action was needed “to prevent an emergency arising”. However, in many cases, the councils pushed back because no evidence was provided to support the claims and most of the affected structures have since disappeared from the company’s works programme without any interventions, The HRE Group said.

“The strategy was intended to avoid the difficulties that come with public scrutiny”, says Graeme Bickerdike, “but that’s clearly unravelling. These rights were never appropriate for permanent works to structures that were fundamentally fine. Permitted development empowered National Highways to impose its preferred method of managing these assets, whether or not they had historical, ecological or potential transport value. The culture was destructive – straight out of the 1970s.”

National Highways’ head of the historical railways estate programme, Hélène Rossiter, said: “Before carrying out the work we consulted with both of the relevant local planning authorities, which confirmed they had no objections or comments relating to the schemes.

“We infilled Congham Road Bridge in February 2021 because we viewed it as a public safety risk. When we took over management of the bridge it was in a very poor condition and had started moving. We consulted with the local planning and highway authorities beforehand, and they confirmed they had no objection to the works and that the scheme didn’t impact any of their active travel plans.

“Rudgate Road Bridge was infilled in April 2021. It had become a risk to the public, having failed a capacity assessment in 2018. A third party had already infilled the bridge on one side four decades ago, which gave rise to unsafe access for examinations and maintenance, as well as there being ongoing issues with deteriorating brickwork.

“We are in communication with the Borough Council of King’s Lynn and West Norfolk, and Selby District Council, and are continuing discussions with them about the work carried out on the respective structures.”

Historical significance of Congham bridge

The railway line passing beneath Congham bridge opened in 1879, but the original structure was replaced in 1926 – one of six similar projects to benefit from an innovative system of reinforced concrete components and blockwork, developed by pioneering railway engineer William Marriott.

Bridge specialist Alan Hayward, co-founder of the civil engineering consultancy Cass Hayward, said: “Marriott was the engineer, locomotive superintendent and eventually general manager of the Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway. There was probably no other engineer to combine such multiple roles, except for the renowned Robert Stephenson.

“His achievements included the design of locomotives, station architecture and bridges, as well as the early development of precast reinforced concrete. A concrete works was established within the company’s workshops at Melton Constable, predating the facilities of railways such as the Southern and Great Western.

“The Congham bridge used precast jack arches, precast casings to the main beams, precast wall units, copings, bedstones and bricks. It was impressive and more elaborate than the other five he rebuilt, featuring elegant curved wing walls. The infilling leaves only two of its type to survive, both under National Highways’ custodianship.”

Got a story? Email [email protected]